As Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One arrives on Digital, Fandom asked clinical psychologist Dr. Drea Letamendi to give her analysis of the man at the center of the M:I franchise, Ethan Hunt. We know he’s able to climb to or jump from any height, but just what is it that makes Ethan tick?

Read on for what Dr. Drea found…

Ethan Hunt is a reputable, highly skilled field agent with three decades of service in the Impossible Mission Force (IMF), an elite, ultra-secret U.S. government espionage agency tasked with protecting public safety and security. So far, the facts surrounding Hunt’s upbringings, early life, and personal background have been portrayed as generally unremarkable up until his well-earned placement in the 75th Ranger Regiment, a premier special ops force for the U.S. Army. Thereafter, Hunt fully embodied the unconventional job as a spy trainee in the IMF, rapidly upskilling and excelling in field surveillance, weapons mastery, infiltration and extraction techniques, and other espionage tradecraft.

Once placed on the IMF, Hunt earned a reputation for his unmatched talents across specialized intellectual abilities including eidetic memory, lip-reading, and critical improvisation. Becoming an agent means agreeing to these objectives: use any methods necessary to complete each dangerous mission, knowing that at any time if you’re captured or killed by the enemy, your superiors will disavow you. It’s nothing personal. Despite his impressive portfolio, Hunt is nothing more than a willing, disposable tool for the government.

An only child who seemingly lost his father at a young age and his mother at some point during his career, Hunt grew to see the IMF as a parental equivalent, and his fellow operatives as a found family. But corruption exists inside the IMF. Early in his career Hunt lost all his team members to the saboteur and previous IMF chief, Jim Phelps. The incident left Hunt feeling disillusioned and betrayed by his leader, but it only drove his resolve further toward preserving the public good, even if it meant going above the IMF.

Decades later, the resurfacing of an enemy known as “Gabriel” reignited memories of a sordid past with the IMF. Gabriel murdered Hunt’s partner, Marie, and Hunt was blamed for it and forced to join the IMF to avoid prison. We wonder if Hunt’s overt enthusiasm for his work originates from these unrepaired wounds. Are the high-speed chases, breathtaking aerobatics, and death-defying stunts merely outlets for Hunt’s unresolved grief? A never-ending distraction from his guilt? Or direct self-punishment for the lives lost under his watch?

High-level espionage requires incredible risk-taking and a disposition to stomach violence, injury, and near-death exposures. Hunt’s personality is well-matched to his profession – he runs toward danger, not away from it. But did Hunt’s eagerness for thrill simply evolve from being exceptional at what he does, or is a profession in espionage just the perfect outlet for him to entertain a deviant personality?

Early in his career, Hunt finds himself involved in missions deemed highly critical and life-threatening. As a top field agent, he infiltrates enemy grounds, retrieves classified intel, and neutralizes targets hands on. He doesn’t hesitate to run into perilous conditions or take high-risk choices if it advances the mission. Over time, he pushes his body toward increasingly more challenging feats and stunts. To the awe of his team, he’s wrestled counterspies on top of a moving train, performed multiple high-altitude skydive jumps, leapt across skyscrapers, clung to the side of a massive military grade plane at takeoff, and BASE-jumped off a speeding motorcycle from a 7,000 feet elevation (which is categorically the most dangerous stunt attempted in the series).

Even when on a supposed relaxing vacation, Hunt seeks heart-racing action. He enjoys free-climbing, cliff-diving, and fast driving. Hunt’s lifestyle is similar to someone with a “T-Type” personality. According to clinical researchers, T-Type individuals gain stimulation from excitement-seeking. Extreme sports participation taps into their need for uncertainty, novelty, ambiguity, and unpredictability. But to be clear, Hunt and his highly aroused peers aren’t hankering for recklessness, uncontrollability, danger, and the excuse to harm others. Quite the contrary: the majority of T-Type folks get enjoyment from attaining control in a conventionally uncontrolled environment. The challenge comes from mastering agency of the body as it endures big changes in speed, force, and novel sensations. Psychologists note that extreme sport participants are careful, well trained, well prepared, and self-aware, and prefer to remain in control.

What’s the real cost for Hunt and other Type T’s? First, risk-taking causes real changes in the brain. Extreme sports enthusiasts experience releases of adrenaline and dopamine during stunts, and these chemicals cause a quick rush of exhilaration followed by intense and longer feelings of pleasure. These emotional waves contribute to a powerful high—which is why extreme lifestyles can be addictive. Often, persons with T-Type traits seek increasingly bigger risks to achieve a rush, not to mention basking in social rewards in the form of others’ awe, admiration, and envy. Mundane activities (in Hunt’s case, a desk job, or when he stepped away from field work to supervise trainees) are boring, glamour free, and cause long-term languishing. Of course, the real, inevitable consequence of pushing the edge is the unspeakable outcome of a foreshortened future. Type T’s have shorter life expectancies.

“Despite the public’s perception, extreme sports demand perpetual care, high degrees of training and preparation, and, above all, discipline and control. Most of those involved are well aware of their strengths and limitations in the face of clear dangers.” – The Lancet

Personality types can play a major role in someone’s likelihood for choosing risky jobs, hobbies, and lifestyles in general. People who have high levels of neuroticism—a combination of anxiousness, depression, self-consciousness, impulsiveness, and deep uneasiness—are sometimes likely to turn to risk-taking. This is why sometimes the “T” in Type T personality refers to “turbulent.” They externalize the turbulence on the inside. Hunt, as confident and steady as he is on the surface, may wrestle with deeper anxieties and restlessness when set stationary. That is, when not in the game, Hunt notices his own loneliness, numbness, aimlessness, and guilt. Adrenaline and action silence feelings of responsibility related to Marie’s death. How many casualties have been a result of his involvement in the IMF? Are his methods justified? Does his relentless drive render his team more vulnerable?

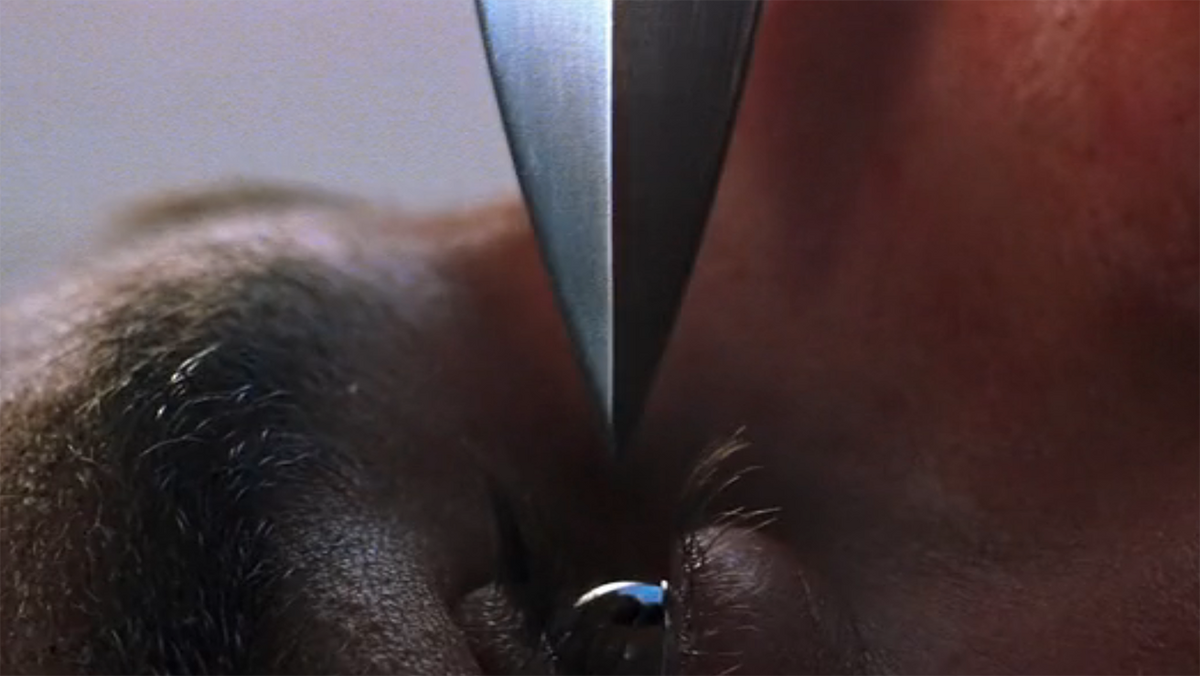

A sense of Hunt’s instability is revealed when he faces off with former IMF agent turned terrorist Sean Ambrose. After an intense standoff, Hunt has Ambrose at knifepoint, with a clear advantage. Yet Hunt tosses his knife aside so that he can fist-fight with Ambrose and beat him senseless. Though Hunt chooses not to kill unless in self-defense, his actions show a desire for intimate brutality. He experiences his own body like a weapon or tool, welcoming dangerousness as he closes a gap between himself and his assailant. He needlessly extends the danger, searching for the edge and pushing himself past it. Hunt ultimately survives this risky choice, but it was nearly a fatal one.

The reality is that humans are not well-designed for sustaining recurring traumas. Typically, exposure to repeated violence leads to mental hyper-vigilance and the inability to accurately register safety. Hyper-vigilance is the elevated state of constantly assessing our surroundings for potential threats. It’s like being on guard at all times, never quite feeling at ease. Again, Hunt appears poised, but his brain is likely ultra-busy surveilling the environment for danger.

Ultimately, Hunt is masterful at silencing the noise inside. He can likely find steadiness between the storms, and he’s shown potential for adapting alarm into agency. In high stakes situations, Hunt doesn’t allow the nerves to get the best of him. He’s mastered the psychological skill of self-regulation, responding to the demands of his external experience and redirecting the tension toward his focus, his discernment, and his determination. To successfully combat hyper-vigilance, Hunt employs self-monitoring (practicing a consistent awareness of his state of mind, feelings, and needs), self-instruction (self-talk; driving his actions with intention and autonomy), goal-setting (understanding what will make him feel in control and knowing the steps it will take to get there), and self-reinforcement (celebrating his own wins).

“You know, that was the hardest part about having to portray you… Grinning like an idiot every fifteen minutes.” – Sean Ambrose to Ethan Hunt

Balance is key. Adrenaline-seekers can be psychologically healthy, especially when well-disciplined, well-trained, and clear headed. Small doses of (safe) risks are actually recommended by therapists. Risk can have some positive consequences on the brain because of the functional processing of feel-good chemicals. For instance, high-intensity running can kickstart dopamine activity, which can ward off depression and reinvigorate one’s enthusiasm for everyday matters in life. Risk-taking also stimulates a state of mind needed to energize a person when starting a new career, initiating relationships, or launching a new chapter in life. For Hunt, returning to field work after years of inactivity, during which he was training new agents, brought back his fervor and his focus. Field missions give him a hit of purpose, a reminder that he’s highly valuable, uniquely talented, and capable of greatness.

Hunt may be best known for his physical feats. But mental fortitude is half the job. Successful espionage agents tend to have genial qualities; they need to be persuasive, trusting, and likable. In addition to having general intelligence (book smarts), they must have high social intelligence, which is a person’s ability to understand, predict, and manage interpersonal relationships. They perceive and predict other people’s feelings and behaviors in order to best influence if not manipulate them. Furthermore, spies frequently carry pathological personality features that pave the way to successful espionage, such as an aptitude for duplicity and a desire for control. Their moral reasoning is flexible and their goals are self-interested. This is why employing spies is risky: their self-interests and can eclipse their deference for authority.

Espionage is among the top 10 professions that tend to attract people with psychopathic personality traits (in good company with physicians, Special Forces operatives, law enforcement, attorneys, journalists, and politicians). This repertoire underlies three main psychopathic tendencies: attributes of superficial charisma, inflated confidence, and staying “cool under fire.” And though Hunt is certainly brazen, cool under pressure, and supremely confident in himself, he isn’t faking his charm. A true Machiavellian wears a mask of a friend; they are cunning, deceptive, exploitative, and charming for their personal gain. Hunt’s kindheartedness is unquestionably real and runs deep. He’s genuinely caring about others and holds great respect surrounding his responsibilities in servicing public safety, which sets him apart from agents who let greed, power, and remorselessness drive their vision.

Hunt’s ability to remain calm under pressure may have less to do with callousness (observed in psychopaths) and more to do with adaptation and skilled self-management. It’s true that Hunt taps into something many of would struggle with—emotional detachment and intense depersonalization, and a willingness to do harm as a part of the job. Hunt engages in harm only when it is justified for a higher moral purpose.

Healthy features that can curb personality-related pathology are called countervailing traits. Think of our disposition as a thermostat; when our maladaptive patterns get uncomfortably “hot,” similarly enduring positive traits can “cool” us down. For instance, Hunt likely carries genetic factors influencing anti-social traits like impulsivity, novelty-seeking, aggression, deceitfulness, and doggedness—in fact, these are the dispositional elements that make Hunt a superb spy. Hunt also bears dominant offsetting personality characteristics can outweigh the “strength” of those influences in order to keep him level-headed. These characteristics include having calm temperament, a strong sense of responsibility to do good, tough mental tenacity, and a genuine warmth toward others. He may be an adrenaline-seeking alpha, but his sincerest wishes are to protect the public above all else.

We know these positive features are strong parts of Hunt’s psychology given his actual choices, arguably forming his core values and driving forces more than any of the masterful qualities that make him a superb operative. Being assigned an “impossible” mission assumes a high-impact and grandiose task, but Hunt’s groundedness keeps him from getting selfish, egotistical and greedy. Hunt’s groundedness, compassion, and humility are offset his pathology and remain his most remarkable qualities. Groundedness does not eliminate Hunt’s ambition and edginess; rather, it situates these qualities and channels them in more adaptive ways. When his ego sparks wild ideas, his groundedness keeps him admirably sensible, realistic, and unpretentious.

Furthermore, staying grounded can offset burnout and disillusionment, which are constant occupational hazards in espionage work where jobs can last months and entail intense and high-stakes responsibilities and angst about one’s disposableness. Hunt shows incredible steadiness when incarcerated for the charges of killing six Serbian nationalists. His internment at Rankow Prison, a dangerous Russian corrective facility known for its harsh regimes and human rights violations, is an undercover guise as part of a larger mission to collect terrorist intel. Hunt’s patience and tenacity in carrying out this sentence seemingly far outweigh any desires for personal gain and unscrupulousness.

Several years into his time with the IMF, Hunt meets and falls in love with Julia Meade. They’re a perfect match. She’s a devoted nurse who has a flair for daring, outdoor excursions. They have an instant connection and become engaged within a couple years of dating. During their courtship and cohabitation, Julia is unaware of Hunt’s actual profession. As far as she and her family understand, Hunt is a systems analyst for the U.S. Department of Transportation, which is really the cover legend assigned to him by the IMF. Julia sees Hunt’s good-natured qualities, his warmth and kindness, and his adventuresomeness. She is the only person in Hunt’s life who recognizes his value outside of his professional identity, who shows him unconditional love completely unrelated to the successes and failures of his missions. When they are together, Hunt savors the fleeting but sincerest moments when he forgets about the pressures of his high-stakes job.

“What I see in Julia is life before all this. And it’s good.” – Ethan Hunt

Once Hunt establishes a personal relationship, he introduces heightened risk for discovery, more intense compartmentalizing, and conflicts of interest. From that time on, a separation must be maintained between his secret “spy” identity, with its clandestine activities, and his “non-spy” public self. The covert activities inescapably exert a powerful influence on Hunt’s overt life.

It isn’t long until Julia notices her fiancé’s secretive behavior. On the night of their engagement party, Hunt is pulled into action to extract an IMF agent who’s been captured by trafficker Owen Davian. It’s one of his own trainees, agent Lindsey Farris. His first reaction is to refuse the mission, to preserve his new life with his fiancé and to pursue the plan to work for IMF as a training officer, out of the line of fire. But Hunt’s strong sense of responsibility and his loyalty to his fellow agents draw him back into active duty. He marries Julia in a spontaneous and private ceremony, and immediately returns to duty. In a harrowing rescue attempt, Hunt and his team successfully save his colleague from the arms dealers, but Farris dies soon after from the microbomb Davian planted in her brain. The tragedy sets off a series of major disappointments and grieving for Hunt and his newly assigned team members. According to the IMF, Hunt’s failure was his inability to extract enemy intelligence during this assignment; his decision to focus on saving his fellow agent was seen as wasteful. Hunt has been trained to keep things impersonal. Yet he’s putting people before the process, which is seen as subordination to his superiors.

Hunt’s team later manages to kidnap Davian, who regains consciousness aboard a plane. Hunt goes to work interrogating Davian about the whereabouts of an elusive item called the Rabbit’s Foot. Davian is savvy, and immediately threatens back, telling him that he found Agent Farris’ death pleasurable and that he’d find Hunt’s wife. “…and I’m going to hurt her, I’m going to make her bleed and cry and call out your name.” In hearing this threat, Hunt loses his clarity and diplomacy. In a seething rage he lunges toward Davian and hangs him over the plane’s open hatch, threatening to drop him 25,000 feet to his death. Hunt’s most trusted companion, Luther Stickell, tries to de-escalate him. “This isn’t you,” he coaxes, attempting to bring Hunt back to earth. Here, Hunt is confronted with his deepest and most realistic fear. He has more to lose than his own life. Being out of control is not only atypical for Hunt, but it’s a feeing he despises.

Davian has hit a nerve, triggering and enlivening an insurmountable dread within Hunt’s psyche. Hunt’s worst nightmare is that his efforts to protect the world would inevitably lead to his wife’s death. His exaggerated sense of responsibility for the wellbeing of others is fired up. For a man nearly always in control, the feeling of helplessness overwhelms him. The resulting reaction is a secondary wave of emotions: outrage, arrogance, brutality. He’s unhinged and out of control. His choices are erratic, not to mention unhelpful and discordant to the team. Ultimately, Luther’s persuasion works, and Hunt does not kill Davian. But the incident reveals to Davian that Hunt’s weakness is something that can be weaponized by his enemies.

How does Hunt always seem to know what to do? And how does he know it’s the right thing to do? Hunt nearly always accepts his mission, but he almost never follows IMF’s instructions consistently. To Hunt, the means matter just as much as the ends, and his mental tenacity allows him to find the most humane and just solutions in each crisis. He’s earned the reputation of a rebel agent, a rogue who isn’t deterred by the threat of being disavowed by the IMF.

Hunt’s strong commitment to “doing the right thing” can be explained by the Moral Foundations Theory, a set of psychological principles that helps to clarify why some of us are like Hunt and some of us are like the duplicitous Agent August Walker. We have six innate moral foundations (sometimes called moral “taste buds”) that drive our moral reasoning: Care, Fairness, Loyalty, Authority, Liberty, and Sanctity. Like D&D characters, we can be categorized according to core organizing principles that drive our quick, intuitive judgments about others, ourselves, and the world, and you can predict our behavior based on these alignments. Hunt, for instance, is likely to favor principles of Care and Fairness above Loyalty and Authority. He is drawn toward participating in acts that lean into kindness, empathy, and peacekeeping. He’s unwilling to deliver harm unless it’s for the preservation of those integrities. He’ll even honor these principles over Authority, by violating the ethics of respect, duty, and lawfulness to achieve equality and justice.

“Some flaw deep in your core being simply won’t allow you to choose between one life and millions… That’s your greatest strength.” – Alan Hunley to Ethan Hunt

Hunt often puts the welfare of his team members above the needs of the IMF. When recruiting a thief named Grace to the team, Hunt assures her with all conviction, “Your life will always matter more to me than my own.” When facing a moral dilemma, Hunt uses sharp problem-solving and social consciousness to serve the wellbeing of his friends. Quick on his feet, he’s saved colleagues Benji and Luther from the clutches of the Apostles, an international extremist group. His actions lead to a botched mission and a nuclear weapon in the wind, but Hunt will always put his team above all else. Members of the Apostles (formerly known as the Syndicate) are equally principled as Hunt, and equally committed to their core values, but they favor other moral domains. Agent Walker, under the alias John Lark, colludes with terrorist mastermind, Solomon Lane, and is willing to kill innocents, infiltrate the CIA, and make nuclear weapons accessible to free agents. To the Apostles, inciting a revolution by spreading global fear and mistrust is aligned with an ideology grounded in the moral principles of Liberty and Sanctity, suggesting they seek freedom from the current world order and its corrupt, “diseased” leaders by any means. Willing to betray, cheat, and harm others, Walker and his peers violate or downgrade ethics of human Care and Fairness.

“There cannot be peace without first, a great suffering. The greater the suffering, the greater the peace.” – Solomon Lane

As it turns out, our moral alignments run deep! Brain scan studies have mapped distinct moral leanings onto different parts and functions in the brain. And putting our moral principles into action can be an effective way to counter troubling feelings of disenchantment, depression, and helplessness. When we do things that invigorate our values, we revitalize hopefulness and confidence. Hunt instills a positive attitude with his team by appealing to the moral alignments they share; by encouraging them to embrace the compassion they have for humanity and toward altruism (Care/Fairness) as opposed to appealing to their interest in serving the U.S. government or elevating one’s nobility (Authority/Sanctity). The mission matters because the team matters.

Hunt’s assigned team can be irregular and inconsistent as far as members go, but the IMF is small enough that he forms relationships with agents who routinely support him. Over three decades, he’s developed a strong synergy with hacker Luther Stickell and technician Benji Dunn, the masterminds who operate behind-the-scenes so that Hunt can perform hands-on enemy infiltration and neutralization, often down to the literal wire. Spy bonds run deep, but are they healthy?

Trauma bonding is a term psychologists use to describe an attachment between people that stems from repeated cycles of trauma they experience together. The bond is considered a coping mechanism in response to abuse and exists due to the underlying imbalance of power between an abuser and an abuse survivor. A trauma bond can occur in the realms of romantic relationships, platonic friendships, hostage situations, manager and direct reports, and cults. Trauma bonding is most commonly found in complicated entanglements between hostage and kidnapper, within intimate partner violence, and in abusive parenting.

Some forms of trauma bonding are less intentional and less recognizable, but can be insidious nonetheless. They manifest as groups (cults) and in sanctioned organizations (fraternities and sororities), where there may be abusive behavior muffled by periods of fun events and rewards. Analogously, the IMF is intentionally designed to create blind loyal and unconditionally committed agents who risk their lives for a greater cause; they are repeatedly exposed to actual life destruction as well as potential imminent events such as terrorist attacks, global nuclear warfare, and digital anarchy. The IMF may not be the enemy, but they make vital decisions about the extent of hazardous exposures Hunt and his team must face. When the team is successful, IMF leadership dishes out praise and rewards, which inevitably comingles positive and negative experiences: mistreatment and validation.

“A normal relationship isn’t viable for people like us.” – Luther Stickell

For a trauma bond to persist, a power differential must exist between the abuser and the victim. With ongoing intermittent (on and off) punishment and rewards, the abuser/dominator confuses the victim and sends their self-esteem into a whirlwind. Hunt, for instance, is repeatedly told by his superiors that he’s expendable, reckless, and self-serving, and is disavowed multiple times (i.e., punishment), but, after every fallout, the IMF also patterns effusive compliments about Hunt’s talents and offers him flattering, exciting missions tailored just for him (rewards). Much like abusive romantic relationships, the IMF creates a false sense of a “we” in the relationship, emphasizing the importance of Hunt’s loyalty to them and making him wonder, “what else can I do? Where else can I go?”

Hunt and his fellow agents find it safest to separate from any friends and family, further isolating themselves and identifying more closely with IMF’s harsh criticism and blame, manipulation, secrecy. This hot and cold progression can profoundly impact a victim’s worldview, perception of reality, and their relationship with themselves. Over time, Hunt may question how he personally matters in all of it. Trauma bonding is linked to several adverse mental health and well-being outcomes. The power imbalance can lead to the victims developing a negative self-image due to feeling controlled, restricted, and isolated from other people with the exception of their abuser.

“I always take care of my friends.” – Ethan Hunt, to prisoner friend Bogdan Anasenko

Harm trickles down. In high-stress situations, the potential for Hunt to emulate his IMF superiors and unknowingly pass on the abuse is elevated. When feeling helpless, taking control and redirecting the belittlement toward others is often occurred. Breaking a trauma bond involves nurturing oneself and their relationships. Hunt, however, leans into his moral integrity and finds ways to interrupt the systemic pattern of abuse, by giving his team the real choices, autonomy, and personal encouragement to pursue challenges not because someone of authority told them to, but because it is the right thing to do.

When the smoke clears, Hunt typically checks in with his compatriots. Trauma debriefing is an effective way to offset long-term impacts of challenging events and prevent deeper post-traumatic stress. For instance, after breaking out of Rankow Prison as part of an unercover mission, he connects with fellow agents Jane Carter, William Brandt, and Benji Dunn. During their debrief, Hunt pauses to acknowledge the challenges the team faces. They were each were dealing with a personal “ghost” of their own. Carter lost a beloved partner in the field to a diamond dealer, Brandt holds onto excessive guilt for not being able to protect Hunt’s wife, and Dunn is in shock as this is his first field mission. This is also Hunt’s first mission since placing his wife into protective custody and faking her death. Loss of life is acknowledged, not dismissed. Hunt doesn’t expect his agents to be unemotional or cold-hearted. His resilience is influenced by his own sacrifices and losses, and he understand that his team members can also feel grievances and pain. He states the obvious, that no matter how angry or vengeful they become, they cannot get their fallen agents back.

“Did it make you feel better? When you killed the man who killed your wife?” – Jane Carter to Ethan Hunt

Hunt also forgives his team for their humanness. They were unprepared and in the dark. The IMF abandoned them. “The only thing that functioned was this team,” he says. He knows his teammates must maintain their resilience and mental health, and not lose their way. The subtext is found in Hunt’s own self-determination to process his losses and not let his grief get the best of him.

Hunt’s continuous, lifelong involvement in covert activities has an inescapable and powerful influence on his identity. Spy life is all about ongoing efforts at concealment, compartmentation, and deception, and it’s easy for an agent to lose track of their true self amidst the falsehoods. Psychologists who specialize in U.S. Intelligence warn that the process of constant self-transmutation—or shapeshifting—in both appearance and personality, can be mentally draining. You can lose sense of who you are as a person. With Hunt, being a prodigious operative gets entangled with his sense of self. He can no longer separate his occupation from his identity. He can only relate to the world through the unabating lens of threat vigilance. Enemies of the state become his personal enemies. There is no divide.

Hunt lives inside a paradox; he’s driven by his own ideals to protect the innocent, to cauterize insidiousness in the world, to preserve the liberties of people, and yet his actions create dangerousness for the people close to him. In order to liberate the society he cares about, Hunt must stay confined in his prison of emotional detachment. The ultimatum resulting from Gabriel’s terror is a sobering perpetual punishment: serve the IMF indefinitely, or spend a lifetime mourning the innocent souls he is unable to save.

“Hunt is both arsonist and fireman at the same time.” – Alan Hunley

Ethan Hunt is a shadow without his agent identity. He can survive being disavowed, poisoned, and tortured, but the responsibility to bodyguard the entire global society is an insurmountable burden that may eventually destroy him.

Related New

Related