In celebration of May the 4th, AKA Star Wars Day, look for several stories exploring aspects of Star Wars this week at Fandom!

Here, we asked clinical psychologist Dr. Drea Letamendi to give us her expert analysis of Din Djarin, on the heels of the third season of The Mandalorian.

Navigating the universe during the era of the New Republic can be quite a perilous space adventure all on its own. Though the oppressive Empire has been defeated and the Galactic Civil War is over, all across the galaxy planets are forming their own self-regulating systems, and remnants of Imperial authoritarianism continue to persist on distant worlds and lawless frontiers where its new leaders have little control. With the central government demilitarized, criminal organizations, mercenaries, and pirates boldly settle into the territories vulnerable to scum and villainy.

It is under this disorder that deputized Bounty Hunters rose to importance in interceding and upholding any kind of justice—but traveling from planet to planet and retrieving bodies, dead or alive, does take its toll. The lifestyle comes with a price. The story of Din Djarin and the Mandalorians foregrounds the less visible injuries of prolonged war, especially on cultures struggling to preserve their way of life following displacement and genocide. Djarin is undoubtedly capable of surviving battles, but how does his psychology stand up to the increasing factionalism and post-war disillusionment closing in on him? Does he choose to withdraw into the shadow of his fortified beskar armor, using obscurity as a blindfold against the harms he participates in? As he begins to question his role in a flawed and fractured system, Djarin experiences a cultural revitalization, recognizing how moral survivorship is inextricably tied to bonds and allegiances toward people, not creeds.

Djarin rose to prominence during the fall of the Galactic Empire, serving as an esteemed member of the Bounty Hunters’ Guild, a government sanctioned organization that regulated and expedited bounty hunting trade. Bounty hunters in the Guild – at least those who are successful – are generally independent, resourceful, and resilient. In addition to these psychological traits, bounty hunters must have a sense of ruthlessness and amorality toward their work, forming little personal attachment or any meaning to their transactions. Hunters follow the money. As independent contractors, it often does not matter to the hired hand what the target did or where they will end up.

Bounty hunters are required to follow the Code – essentially, they must not interfere with another hunter’s mission, take their bounty, or willingly harm one another. At the peak of his career as a bounty hunter, Djarin is by the book. Greef Karga, Guild Master of the Nevarro Hunters, is impressed by Djarin’s swiftness and expedience. He is reliable. Being a part of Mandalorian culture makes Djarin a key candidate for bounty hunting. His face is occluded by a helmet he never removes in public, creating a sense of mysteriousness and concealment. Moreover, Djarin was raised to respect the Mandalorian Creed, a set of social rules bound by solidarity, loyalty, and obedience.

“I can take you in warm, or I can take you in cold.” – Din Djarin

Djarin’s personality suits a bounty hunter lifestyle, as he is not only persistent with the work, but at times forceful and threatening. Though he belongs to an orthodox Mandalorian clan and shaped to have respect toward community values, Djarin spends most of his time on his own. He is a lone gunfighter, often silent and perceived by others as terse and aloof. An unruffled and emotionless warrior, he chooses weapons over words. As his work requires him to operate in the seedy underworld, Djarin has grown stony and rough, emotionally detached from the actions required to handle criminals and mudscuffers.

Djarin, however, can also be extremely loyal and dependable, as he was raised among a clan of Mandalorians that honored staying true to one’s word. He has little interest in forming relationships unless they are purposeful ones, such as a reliable mechanic who repairs his ship, an Ugnaught farmer who helps him negotiate with Jawas, or a Frog Lady who imparts information in exchange for passage to the estuary moon of Trask. Though Djarin is quite confident and successful as a bounty hunter, he is particularly shy under all that armor. He may learn the details of his adventurer companions, the planets they are from, their histories, and even the traumas they endured, but they learn nothing about him and his dark past.

Djarin was raised on settlement among people native to a terrestrial planet called Aq Vetina, which was raided by the Confederacy of Independent Systems during the Clone Wars. Separatist battle droids attacked Djarin’s village, killing his family and eradicating the population. The Mandalorians of the Death Watch intervened, saving Djarin and taking him in as a foundling. As an adult, Djarin holds startling memories of the battle that killed his family, remembering bits and pieces of the event – the most horrifying moments as well as the most comforting. He recalls the sounds and images of explosions and gunfire, being held in the arms of his father as the family flees from the tireless metal monsters, his mother’s hand cradling his head as she says goodbye, the darkness of the hatch his parents hide him in, and the sound of the blast that kills them. Djarin vividly remembers his rescue. He recalls looking upward into the ray of light pouring through the hatch doors, his face fully exposed and lit by the sun. Djarin also vividly recalls his faceless rescuers, the Mandalorians; he is greeted not by comforting eyes or a safe smile, but by the t-shaped visors and angular helmets worn by the fearless warriors who will become his new family.

“The foundlings are the future. This is The Way.” – The Armorer

The Death Watch eventually divided and a faction became the Mandalore Resistance under the leadership of Bo-Katan Kryze, allies to the Jedi and the Galactic Republic. Djarin, however, was raised as a part of the Tribe, a very private and secluded clan that honors the doctrines of the Children of the Watch. This clan follows orthodox practices and forbids members from removing their helmet in the presence of others.

The Creed requires Mandalorians to take care of orphaned or lost youth (called foundlings) until they were reunited with their own people or came of age. Each Mandalorian clan believes that when members follow the Creed, they experience true freedom and happiness.

As a foundling, Djarin was indoctrinated into these followings. When foundlings come of age, it is time for them to officially become initiated and close themselves off from the world. The swearing ceremony is one of their most sacred rituals, and includes banners with clan signets, ceremonial drumming, and a baptism. The foundling stands in water, recites the words of the Creed and swears to walk the Way. A helmet is placed on the foundling’s head, and the tribe chants “This is the Way.” The foundling then swears to never remove his helmet from this moment on.

Djarin’s childhood trauma is intertwined with the loss of physical touch and the shelter of concealment. It is the last time he will feel his face pressed against the face of a loved one, or find comfort from affection and warmth, from eye contact, from the touch of a hand on his head. His new family will never make eye contact, hold him, or give him the expressions of care, approval, or love. Hiding, obscurity, and shadow become integrated into his sense of self. Meanwhile danger and violence are associated with droids. It is this moment that Djarin develops disdain for droids no matter their type or class or programming.

Prejudice is based on incomprehension, ignorance, and fears of difference. An unpleasant experience with members of an outside group may lead a person to form an incorrect or unjustified attitude toward the whole group. Based on his traumatic experience with Separatist Battle Droids, Djarin develops preconceived negative opinions about robots, grouping all members of droids into a mental category characterized as untrustworthy, dangerous, ruthless, and violent. In contrast, Djarin sees Mandalorians as humanized, discerning, and caring, despite their outwardly metallicized and faceless features. To him, the Mandalorians are, historically and culturally, a group of warriors who honor and dignify their violence, while droids are reckless, brutal, and subhuman.

Using psychologist Gordon Allport’s scale of prejudice, we can recognize how deeply affected Djarin is by his bias. We are witness to Djarin’s participation in antilocution (freely expressing his antagonism towards droids or making demeaning jokes about them), avoidance (refusing to take a ride from a droid and instead accepting a much less luxurious form of transportation with a human pilot), discrimination (threatening droids or denying them of the opportunities, rights, and recreation in a droid-only bar), physical attacks (kicking reprogramed, likely innocent battle droids on Plazir-15), and extermination (shooting IG-11 in the head, a violation of the Bounty Hunter’s Guild Code).

“There’s nothing to be sad about. I’ve never been alive.” – IG-11

Djarin’s relationship with IG-11 sparks significant changes in his attitudes about droids. He first confronts IG-11 when the droid is a fellow bounty hunter tasked with destroying the “package” Djarin was retrieving. Once he sees that the package is a small child-like and helpless creature, Djarin decides to betray IG-11 and the Guild by shooting the droid down and destroying him.

However, the Ugnaught Kuiil retrieves IG-11’s flotsam and rebuilds him as a nurse droid, with new base commands to protect The Child. Though they spend more time together with this shared goal, Djarin remains distrusting of droids. When he is seriously injured and trapped in a bunker, IG-11 offers to heal Djarin with bacta spray. This requires Djarin to remove his helmet, and he resists. “No living thing has seen me without my helmet since I swore my creed.” IG-11 assures Djarin that he is not “a living thing,” prompting Djarin to show his face to him. Djarin’s perception of IG-11 as another living being, a peer, shows how he’s shifted away from his initial prejudice.

When the two are yet again attempting to escape their enemies aboard a droid-controlled barge on a lava river in Nevarro, IG-11 offers to sacrifice himself by defaulting to his original program. He plans to wade into the lava and self-destruct at the tunnel gate, killing all of Imperial warlord Moff Gideon’s stormtroopers who await to ambush them. Djarin disagrees with the plan, and IG-11 tells him not to be sad, as this is the only way the Child will survive. But when Djarin denies that he feels sad, the droid reminds him he is programmed to detect emotion in verbal communication. IG-11 indeed sacrifices himself to save the group and Djarin remains emotionally moved by his actions, impressed that his droid companion can use his destructive instinct not to slay innocents but to save his newfound friends.

Avoiding intimacy is one of many ways that Djarin deals with his childhood trauma. Encountering something that reminds you of a trauma can cause extreme physical or emotional reactions long after the traumatic situation is no longer happening. This is especially true of childhood trauma. Like many youths who lose their parents or are separated from their caregivers, Djarin may have experienced difficulty forming close bonds or receive nurturing from his new family, the Mandalorians. Choosing the lifestyle of a bounty hunter allows him to stay in a chronic state of detachment, finding purpose (and feelings of achievement) in his work, while also literally traveling from planet to planet as a form of constant escapism. Closeness may stir up positive feelings such as trust, companionship, and protection, but may also trigger upsetting feelings such as abandonment, fear, and rejection. Djarin relies on both cultures—bounty hunting and Mandalorian—to remain distant from others, hiding behind his toughness, his beskar helmet, and his ideology to remain closed off to the universe.

“The catastrophe you fear will happen, has in fact, already happened.” – Donald Winnicott, Psychoanalyst

Despite growing up in a “we” environment, Djarin has developed an “I” perspective as a psychological protective measure. Hyper-independence is a trauma response characterized by frequently making decisions and accomplishing things without the support of others. Hyper-independence occurs when we choose to be completely independent of everyone, holding beliefs that we can only rely on and trust ourselves. Overachievers often are the way they are due to some overlap with interpersonal trauma. Some symptoms of hyper-independence include taking on too much in our lives, refusing others’ help, and holding a guardedness in relationships. Hyper-independent people tend to be secretive, and keep their thoughts and intimate feelings to themselves. Hyper-independent people also dislike the characteristic of “neediness” and even resent internal feelings of reliance on others. The reassuring self-talk typically sounds like this: ‘I need to protect me, and no one is ever going to do this to me again.’

Self-identity and self-categorization are the ways in which we understand ourselves as individuals in context with our social world. Perceiving and understanding others’ facial expressions is critical to our daily interpersonal communication. Effective social communication relies on recognizing others’ emotions during a conversation or interaction (e.g., recognizing that someone is happy), and is a means of revealing one’s own internal emotional states to the listener (e.g., by smiling at another individual).

There is a strong association between obscurity (masks) and aggression in Star Wars, and a similar leaning occurs in the field of psychology, which has determined through decades of science the negative effects of social anonymity. Across factions, all Mandalorians serve as warriors and wear full-bodied armor. Though some clans take off their helmets in public, those who do not may benefit not only from the physical protection of these armored hoods but also from the psychological protection of anonymity. Facelessness enables the belligerence and conflict fundamental to Mandalorian philosophies.

Deindividuation is the phenomenon in which people engage in seemingly impulsive, deviant, and sometimes violent acts in situations in which they believe they cannot be personally identified. The most common cause of deindividuation is computer-based communication (online networks and forums) which prevent people from being identified, and in turn leads to a feeling of being untouchable and to a loss of a sense of personal responsibility. In its most radical form, facelessness on both ends of the communication leads to increased anti-social behavior and a breeding ground for unhinged and extreme beliefs to take hold without any accountability.

Masks not only increase anonymity but reduce objective self-awareness. Behind this barrier, someone may stray away from their internal standards of behavior and replace them with more destructive forms of interactions. Anakin Skywalker’s transition to Darth Vader is a quintessential example of the deterioration of human empathy and an increase of hostility due to physical disconnection between him and the world. Wearing a helmet and mask suppressed Anakin’s expressivity, distancing him from other people and lessening the impressions of the self. In the 60’s and 70’s, social psychology experimenters who put their subjects in KKK hoods (for science!), found that their study subjects administered more shocks to others compared to subjects without hoods, ostensibly due to the loss of personal responsibility and the connection to a hostile identity. Furthermore, facial mimicry—the neurobiological phenomenon of imitating sub-threshold microexpressions—is also crucial for social communication because it indicates reciprocal emotional understanding. In other words, we smile when we see another smiling face, and frown when we see an angry face, which enhances our concepts of ourselves and one another.

More modern scientific explorations further emphasize how important our facial expressions actually are when it comes to empathy. Recent studies on increased use of face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic highlight the relationship between self-expression and face coverings. When someone’s face is occluded by a mask, people are significantly less accurate at detecting the depicted emotion, and tend to perceive the depicted emotion as less intense than intended.

Honoring one’s word is a highly respected code in the Mandalorian Creed. When Djarin takes on jobs, he is committed, steadfast, and uncompromising. Like the bounty pucks he is handed, the people he retrieves, transports, and turns in are like cargo to him. When Djarin realizes that his target is a child, he begins to question his assignment. Typically used to capturing criminals and fugitives, Djarin grows concern for the well-being of the youth he’s captured.

“The Child is small, and I was only able to harvest a limited amount without killing him. If these experiments are to continue as requested, we would again require access to the donor.” – Dr. Pershing to Moff Gideon

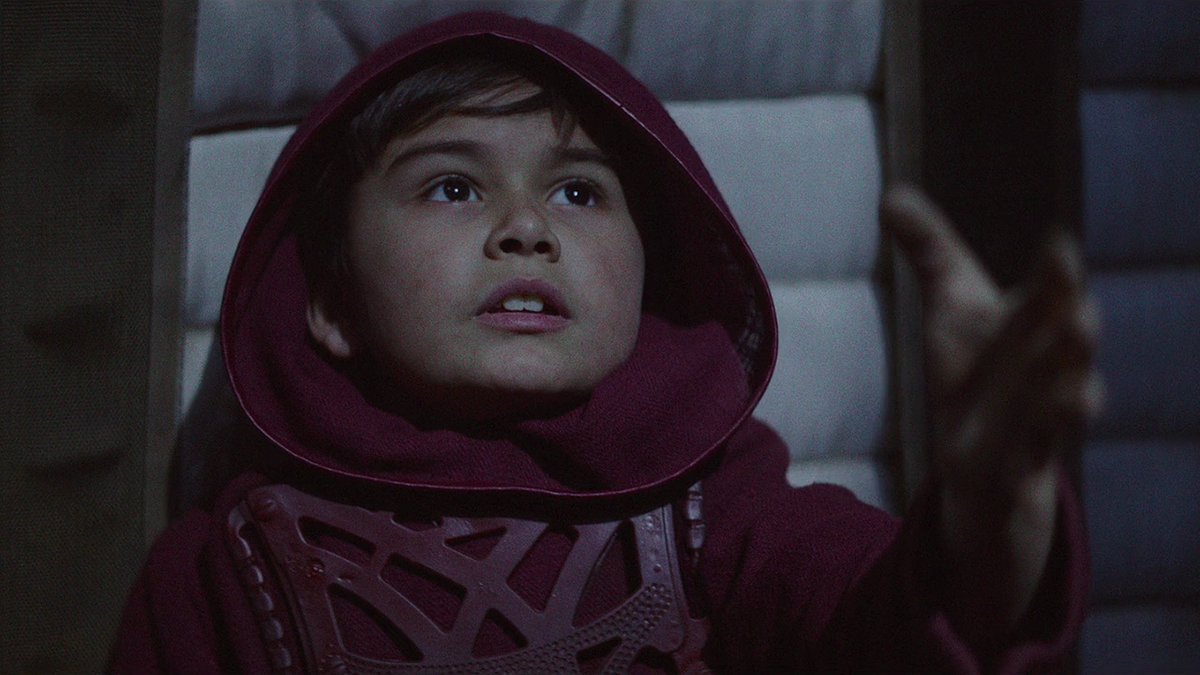

As he spends more time with the Child (later to be revealed as Grogu), Djarin observes the little one’s vulnerability and youth-like qualities, as well as his extraordinary power and uniqueness. When he learns that Grogu will be used for medical experimentation and likely “terminated,” Djarin experiences a little tug on his strongly-held principles, a dissonance within him that he cannot ignore. If he allows Grogu to be taken by the Imperials, he is colluding with their ruthlessness, their abuses, their torture, their horrific eugenics.

Moral distress occurs when you know the ethically correct action to take but you are constrained or prevented from taking it. First identified in occupational settings such as health care, social work, and the military, moral distress can occur in any occupation when workers feel as if they are part of an organization whose mission and protocols seem unethical or unconscionable. Harmful medical practices, shortcuts, and preventable injury or fatalities take their toll on providers. Moral distress tends to be cumulative and can lead to chronic worry, depression, shame, grief, and prolonged guilt. When unchecked, moral distress can have longstanding effects and lead to impairments that leak from the workplace into our personal lives, creating numbness, detachment, and deterioration of the self.

Saving foundlings is considered as the highest honor of the Mandalorian Creed. Djarin, once a foundling himself, once rescued from his assailants, feels a growing responsibility to protect Grogu from harm, abuse, and brutality. His Mandalorian values begin to eclipse his Guild responsibilities. Djarin has a change of heart and readjusts his mission: he is to be a steward of protection and escort the youth to his rightful people. Core to being a Mandalorian is to be a refugee, a wanderer, and a member of a diaspora of people who survive through the passing down and sharing of spiritual practices. After the Purge on Mandalore and the razing of their lands and resources, no Mandalore can really go home, but they can find places of sanctuary and form peace among one another. Djarin seeks to give Grogu a chance for this peace.

Western psychological theorists have argued for decades that anonymity frees people from normative constraints, muting their self-awareness and triggering higher levels of impulsivity, brutality, and even sociopathy. But in some cases, forms of deindividuation can enhance the salience of group membership and their shared norms. “Hiding” oneself behind a mask or helmet can lead to feeling less like others around us, but when exercised as a sacred part of one’s cultural group, as a part of other associated values, it may actually make the experience more integrating, not detaching. Mandalorian clans have their own sigils, colors, and ceremonial banners that serve to augment the ancient ways of their ancestors and are meant to bind and empower them, not divide them.

It is likely that a metal veil does not instill ideas of aggression, but rather, it amplifies any existing tendencies toward the cruelty and harm of others (sorry, Anakin). Djarin may leverage the anonymity of his helmet as a bounty hunter, but he does not harbor sociopathy or superiority toward others, with or without it. As someone who has worn a mask all his adult life, Djarin exemplifies his ways of adjusting to and overcoming this barrier, alongside other members of his clan who must do the same. In post-pandemic studies exploring long-term use of masks, researchers found that in order to be better understood among one another, mask-wearers eventually overcompensate for the limitation, by increasing the volume and expressivity of their speech, using body language such as gestures, and attempting to communicate through other ways. The members of The Tribe are no fools to the subtleties of communication and expressing their opinions, tenets, and needs.

When Djarin takes Grogu to the planet Sorgan, he meets a local villager, Omera , a resilient leader, markswoman, and mother. Despite Djarin’s occluded face, Omera recognizes his integrity and selflessness. She respects his sacred practices, offering him space and solitude when he needs to remove his helmet to have meals. In turn, Djarin does not need to remove his helmet to convey his gratitude, sincerity, and affection for her. To protect Omera’s village from frequent raids, Djarin and mercenary Cara Dune create an allyship with the civilians, and this interdependence reminds Djarin of the bonds he once had with Mandalorians. At one point, Omera asks him to stay with her, and attempts to remove his helmet, but he resists the gesture. In his voice is true honesty and intimacy, but he sinks back into his guardedness and secrecy.

“I don’t belong here.” – Din Djarin, to Omera

In some ways, Djarin is stuck between two cultures—the Mandalorians and the Bounty Hunters; his family and his work; his personal identity and his professional one. Like anyone in his position, he must adjust his approach in order to reduce the growing dissonance within him. That is, he must alter his behavior to be more aligned with his values, or alter his values to be aligned with the actions he perceives as toxic.

Stepping away from his rigidity to be more aligned with Grogu’s needs is an example of Djarin’s psychological adjustment. Despite his objection to removing his helmet in public, Djarin lifts this rule to say goodbye to Grogu when handing him over to his new mentor, Luke Skywalker, allowing his little companion to see his face for the first time. Djarin lets his guard down—and comprises his oath—knowing that Grogu can be soothed and comforted by his caregiver’s unmasked face. This gesture is deeply joyful and painful all at once, as Djarin experiences what it is like for another person to see his emotional expressions after so many grueling years, to bear witness to the traumas and losses he’s endured, and, ultimately, to receive his unfiltered gratefulness for the companionship shared between them.

Djarin proves to be a leader in his own way, not by usurping positions of power among the Mandalorians, but by seeing his value as a mentor, advocate, and crusader. Djarin also shows leadership qualities by supporting the advancement of women and championing their vision when the clans of Mandalore align. He holds little interest in keeping the sacred Darksaber, realizing he is not as attuned to it as his fellow warrior, Bo-Katan. Recognizing the obstacles that Bo-Katan is up against, Djarin explains that she is the rightful wielder of the Darksaber because she bested the beast who took it from him; Djarin does not let tradition eclipse the opportunity of women to rank and excel. His allyship shows that his presence, input, and decision-making are no more valuable than the female leaders on Mandalore.

“He means more to me than you’ll ever know.” – Din Djarin, about Grogu

Djarin’s leadership qualities also emerge as he grows from hunter to mentor to parent. His worldview shifts, as he becomes less interested in his personal gains and more concerned with the needs and safety of others—the people who reclaim Mandalore, the civilians of Nevarro, and Grogu. When the leader of The Tribe, The Armorer, explains that Grogu is ineligible to take the oath because he cannot yet speak, Djarin chooses to adopt Grogu, making him an apprentice and officially a member of the Watch.

Upon taking this commitment, Djarin has learned that being a father is much more than discipline, protection, and ensuring shelter for his offspring. Parenting is also about transmitting cultural values through close bonding, companionship, and affection. This is the way is a phrase that embodies the spirit of handing down traditions, practices, and ideals considered essential to Djarin’s culture, but he knows he must also prepare Grogu for life in a vast universe outside the covert, one that is plentiful with risks and threats, but also with exhilaration and joyfulness. Djarin will be interested in Grogu’s quality of life and potential to experience these discoveries and triumphs free from any ideologies that do not preserve his dignity and humanity. When others saw Grogu as a profit, a collection of genetic material, or a target to be eliminated, Djarin grew to hold unconditional love for Grogu as a whole person, to see immense worthiness in this remarkable little green being. Protecting Grogu will also remain a reparative experience for Djarin, a trauma survivor who has long believed that he did not deserve support or help from other people without a transaction involved. Djarin has done the work to integrate his social identities, that of a warrior, a protector, a political activist, and a father. His help reuniting the clans of Mandalore re-instills the values most meaningful to him, and he ultimately chooses to live them out by settling in a remote, modest homestead with his adopted son.

Related New

Related