Spirited Away, Hayao Miyazaki’s fantastical tale about a girl named Chihiro who finds herself transported to the Spirit Realm, is hands down Studio Ghibli’s most successful film. In fact, it is the highest-grossing film of all-time in Japan, and it’s easy to see why. The film not only offers us a much-needed break from life’s everyday stressors, it also presents us with a colorful cast of memorable characters. From frog attendants to stink spirits to a bird with the head of an old woman, there’s no shortage of unique characters to take in.

But no doubt the character that leaves the biggest impression on viewers is the sullen and silent No-Face, the enigmatic tube-shaped spirit with a Noh mask as a face. Despite No-Face’s limited screen time, he manages to steal every scene he’s in. We can’t help but wonder who or what No-Face might be or might have been –a spirit, a human, or something else entirely? Miyazaki has remained mum on the subject for years, which means it’s up to us to solve this mystery. With Spirited Away now available on Max, alongside the rest of the Ghibli library, we’ve decided it’s time to put a face to the figure behind the mask by dissecting No-Face’s various appearances throughout the film.

When people think of No-Face, the first thing that likely comes to mind is his trademark white mask. But this mask serves as more than just a fashion statement. It’s also a symbol of an enduring Japanese performing art called Noh. In this traditional Japanese stage drama, the main performer wears a Noh mask, much like the one No-Face dons himself. Like No-Face’s mask, the ones worn by Noh performers bear neutral expressions. However, you’d be wrong to assume that their purpose is to conceal the actor’s emotions or face from the audience. In fact, they’re meant to do quite the opposite. Noh masks stoke the audience’s imagination, allowing them to infer meaning and emotion based on how the actor moves and tilts the mask.

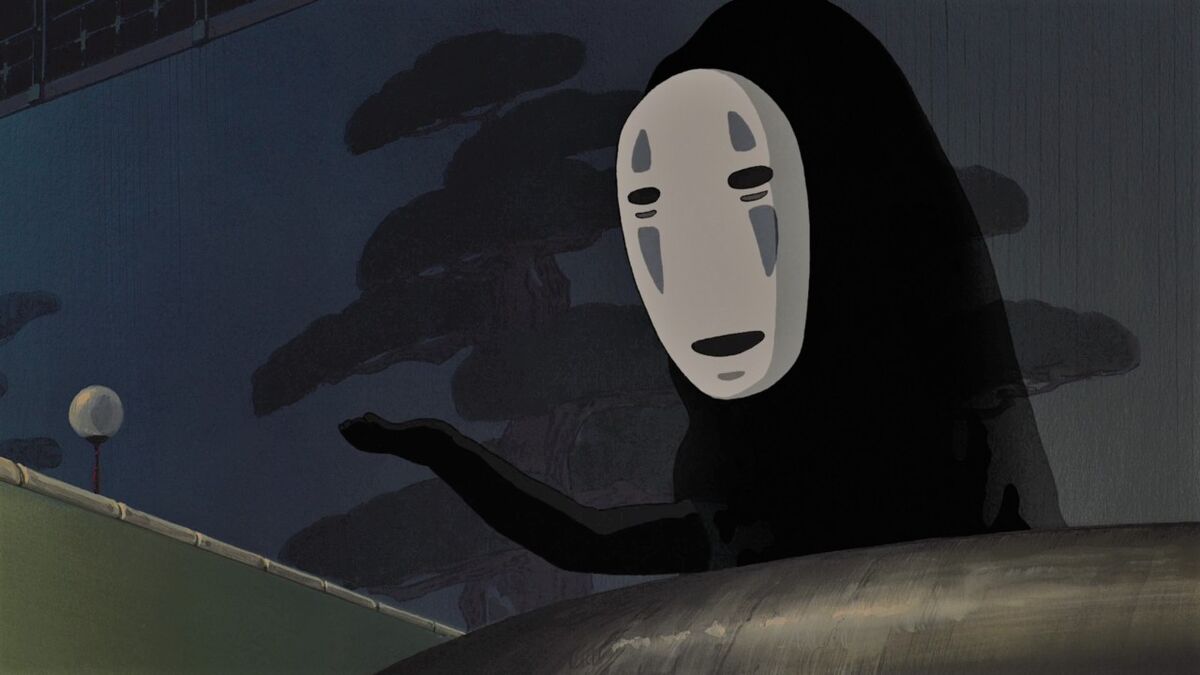

Now, No-Face might not be putting on a one-man show in the bathhouse, but the way he moves and is positioned allows us to envision what he must feel like at any given moment. For instance, it’s easy to see that No-Face is lonely from the moment we first meet him on the bridge. He stands alone and stares blankly as Chihiro passes him by. We have no idea how long he’s been there, but with the way people ignore him, you’d think he was some old stone relic from a bygone era.

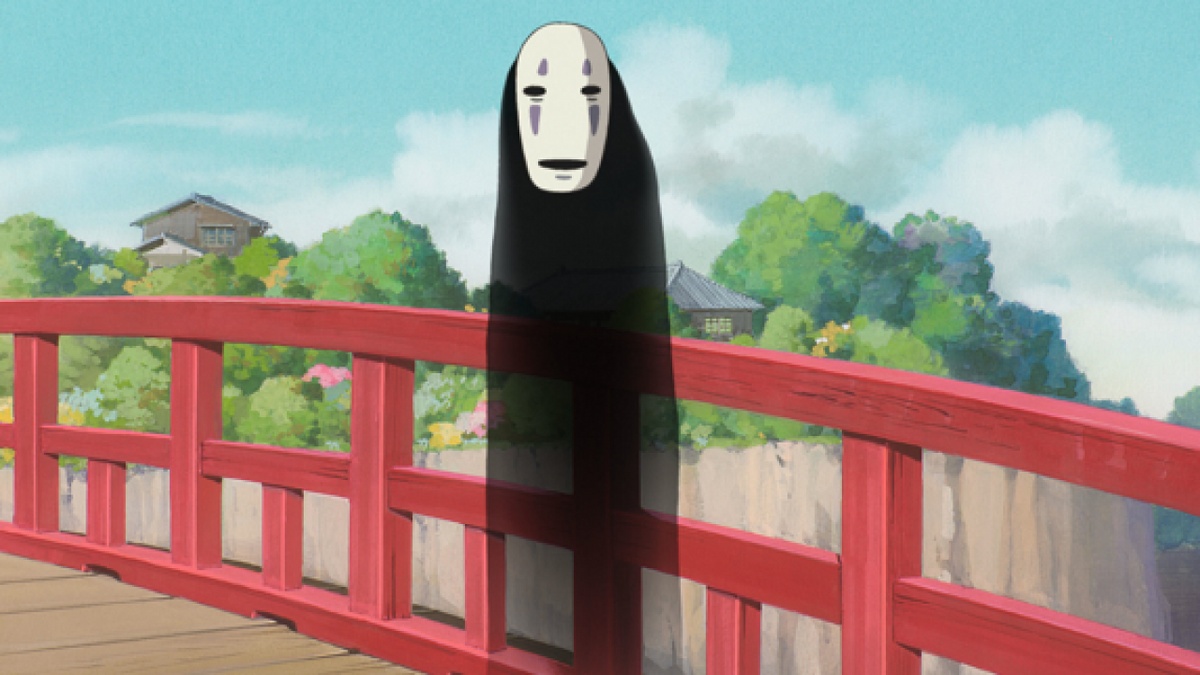

While we don’t believe that No-Face is literally a Noh performer, we do believe that he may represent a longing for the past. It’s no secret that Spirited Away (and most Ghibli films for that matter) seeks to highlight the nostalgia we have for the past, and No-Face is no exception. He stands on the middle of the bridge, nearly transparent. As viewers we get the feeling that he could fade away at moment, never to be seen again. We can’t help but wonder if he’s meant to represent this dying art form’s struggle to survive in the modern day.

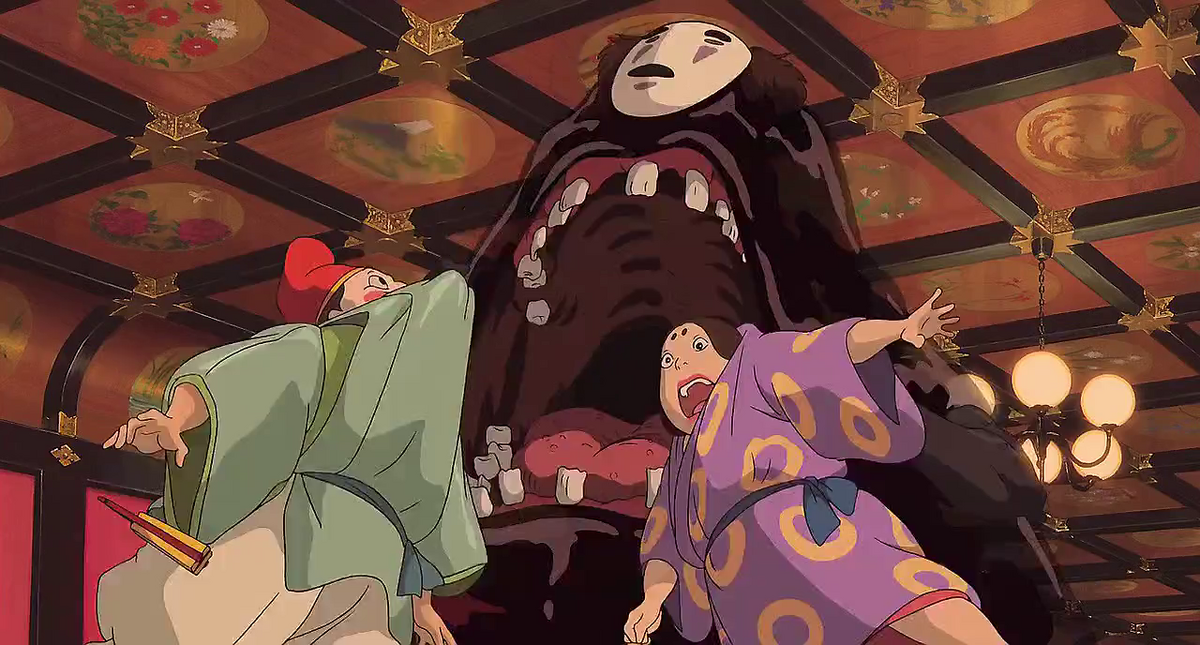

But there’s another historical aspect to No-Face, this one steeped in myth. There is a Japanese legend about a creature called the Noppera-Bo, or the faceless ghost. These mischievous spirits take delight in frightening humans, particularly by appearing as someone they know to draw them in and then erasing their face to give them a scare. Miyazaki, however, flips this tale on its head by having No-Face take on the traits of someone he thinks his victim would like. He also possesses the ability to anticipate a person’s desires and to create objects to fulfill their needs, like when No-Face showers Chihiro’s greedy coworkers with gold. Later in the film, he even gives everyone a fright when he reveals the monstrous mouth–in other words, his true form–hidden beneath his mask.

When you take this and the idea of No-Face representing a bygone pastime, it’s easy to come to the conclusion that he is, indeed, a spirit. He’s literally in the Spirit Realm and Yubaba even calls him a spirit while chastising her staff for accepting his offerings. But as the film constantly reminds us, looks can be deceiving and sometimes a spade is actually a joker. Sure, No-Face appears to reside in a world of spirits, but he doesn’t seem at home there. None of the other spirits take notice of his presence until he starts showering the staff with gold. Not to mention, when Haku tells Chihiro to hold her breath as she crosses the bridge–an act meant to keep the spirits from detecting her–No-Face notices her well before she takes her first breath. Either he’s not beholden to the rules of normal spirits or he’s not a spirit all.

Not long after her parents are turned into pigs, Chihiro finds that she is literally fading away. If not for Haku’s quick thinking, she would’ve disappeared entirely. No-Face, curiously enough, exists in a similar state. The semi-transparent entity seems to fade in and out of locations at will–until you realize that he’s the only “spirit” in the film capable of this feat. It makes you wonder if he belongs in the Spirit Realm at all.

When we first meet the ever-sheer No-Face, he stands on the bridge that leads to the bathhouse. But this is no ordinary bridge. No-Face is shown on this bridge not once, but twice, because it represents the link between the human world and the Spirit Realm. In other words, the bridge between life and death. Don’t forget, Chihiro’s adventure in the Spirit Realm didn’t truly begin until she crossed the bridge to seek out employment under Yubaba.

Like Chihiro, No-Face may also be trapped in some weird purgatory where he’s not quite dead and not quite alive. Except in his case, when he began to fade away, no one was there to help him regain his solid form.

But what could that form be? Well, aside from being bipedal, we see that No-Face is able to create arms and legs that resemble our own and can even leave behind footprints. Later in the film, when his true mouth is revealed (not the one painted on the mask), there isn’t a fang in sight. Not what you’d expect from an entity with such a carnivorous appetite. In fact, No-Face’s teeth have the omnivorous look of a human’s (though he could use a trip to the dentist). All of No-Faces’ defining features are human, albeit distorted.

This could explain why Chihiro catches No-Face’s eye and why he was the only one able to detect her on the bridge. We can only assume that he’d been standing there for some time, waiting on another human to get trapped in the Spirit Realm along with him, longing for that human connection. No-Face spends the rest of the film trying to win Chihiro’s favor. He gives her extra bath essences to combat the stink spirit and tries to win her over with riches beyond her imagination. However, his attempts to win Chihiro over with material possessions backfires every time. After all, Chihiro isn’t there to get rich, but to reunite with her family. And as much as No-Face seems to possess human traits, he doesn’t seem to understand human attachments (or Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, for that matter.)

In a sense, No-Face navigates the world like a child. He seeks approval and praise from everyone, but most importantly from Chihiro, who in all actuality could be his peer. He also changes his values to match those around him and mimics those he encounters, a survival tactic employed on the playground to this day. He even goes so far as to swallow the spirits working in the bathhouse to embody their traits. This allows No-Face to speak, grow taller and take on new personas–much like a child playing dress up.

It’s also a sad attempt to fill the void No-Face feels inside. Children often don’t know how to handle tough situations like being the odd one out. In their overzealousness to prove themselves worthy, they sometimes rub people the wrong way by doing things like trying to force friendships or pretending to be something that they’re not to gain approval and popularity. No-Face truly embodies the latter when he parades around the bathhouse like a mad king, eating to his heart’s content and creating gold out of thin air. He finally receives the attention and praise he longed for–not for who he truly is, but for the mask that he’s slapped on. It’s a hollow kind of praise that does nothing to cure the loneliness in his heart.

So it’s no wonder No-Face loses his mind when he encounters Chihiro yet again–though this time he’s reached the top of the social pecking order–and she turns down his gold. This major snub sends No-Face on a rampage where he devours two more staff members, causing a panic in the bathhouse. Essentially, he threw a tantrum on par with a toddler who’s toys have been taken away. If we continue with our theory of No-Face being a child, then this response makes sense. Left to his own devices for who-knows-how-long, No-Face never received the corrective discipline and nurturing we all need to properly develop meaningful relationships with others. So he watches, and tries to learn on the fly, which leads him to presume that bonds are formed through material possessions.

The only person who can calm No-Face is Chihiro, and she does it not by giving him what he wants but what he needs, which is tough love. She shoots down his offers of food and wealth, and makes it clear that he can’t give her what she desires. No-Face can duplicate all manners of things, but not love.

Chihiro also treats No-Face like a child, asking him where his home is and inquiring about his parents. The same questions you might ask a lost child seen wandering alone in a parking lot. Further taking on the caretaker role, Chihiro gives No-Face a special medicine to help cure him of the monster he’s become. The medicine causes him to have an even bigger meltdown than before. He chases Chihiro through the bathhouse, but by the time he catches up to her, he’s gotten everything out of his system–both literally and figuratively. The medicine’s done its job.

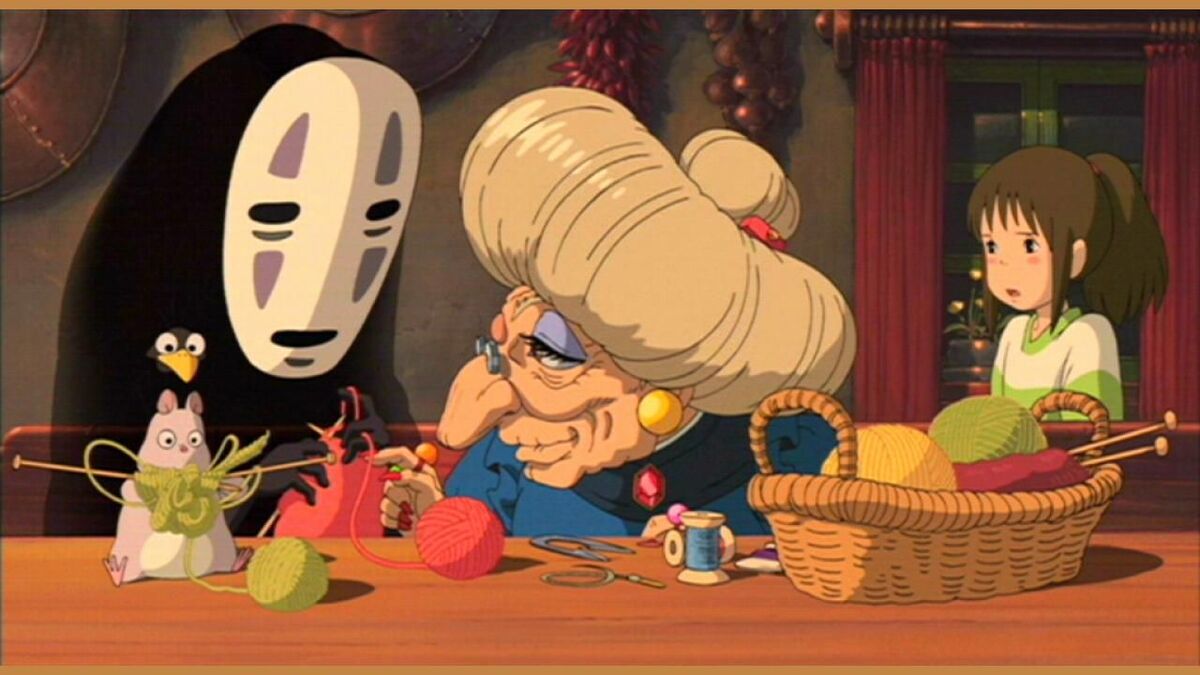

With his body once again empty, No-Face reverts back to his initial form. He’s again unable to speak, but now follows Chihiro around like a dutiful child. When Chihiro travels to see Zeniba to find a way to save Haku, No-Face accompanies her without question. Once on the train, Chihiro even tells him to behave himself, as if he’s prone to mischief.

The whole time he walks silently behind her with his back arched in a way that resembles a child who’s just learned the true meaning of consequences. When he meets the elderly Zeniba, he acts shy and subservient, and once inside Zeniba’s house, he’s on his best behavior, eating and drinking a modest amount and even using utensils. After all, once a kid’s gotten in trouble the last thing they want is to be punished again. At least, not so soon.

It’s clear that he’s still seeking approval, but his approach has changed. Instead of forcing himself on others or trying to anticipate their needs, both actions fueled by selfishness, he tries to show that he’s compassionate by being considerate of others (he even helps Zeniba with her sewing). By the end of Chihiro’s stay, he’s practically adopted by Zeniba, who asks him to stay on as her helper. On the surface, it appears that No-Face has finally gained a purpose, but in actuality, he’s gained a family. And with that our lovable orphan gains a guardian and cures his loneliness.

There’s one final aspect of No-Face we’ve yet to explore–the way he mirrors Chihiro. Drawing on the Noh tradition, if we’re to see No-Face as a blank slate meant to highlight the emotional response of the person who views him, then it stands to reason that he could’ve been showing Chihiro a version of herself. Perhaps, the girl she could have become if she continued on her spoiled path or succumbed to gluttony and greed like her parents.

In that sense, maybe No-Face’s entire purpose was to teach Chihiro a lesson and get her back on the right path. That could explain why he was only interested in her and tried so hard to win her over with material possessions. It could’ve all been a part of a test. It’s clear from the film that Chihiro, who started out as an arrogant brat, was spirited away to teach her to be a better person in the real world. There’s no better way to do that then to hold a mirror up to herself.

Let’s not forget that Chihiro, like No-Face, is also lonely. Her parents were turned into pigs, after all. And she was getting ready to start a new school where she didn’t know anyone–just as No-Face finds himself in a bathhouse without a single friend in sight. When No-Face throws the world’s biggest tantrum and Chihiro calms him down using the medicine, you could say that she was, in fact, calming her own nerves. It’s only then that she’s able to find No-Face a forever home and save her parents. In that sense, the whole film’s actually about Chihiro’s struggle to overcome herself, the resentful monster growing within her.

If No-Face truly is a blank slate that reflects our impressions and expectations, then perhaps he appears differently to everyone, including to each one of us. A parent or older sibling might see No-Face as a child. A little girl might see him as a ghost and another might see his wide mouth and declare him a monster. Still, others might view him as timid and shy or even mischievous. Perhaps that’s the point, and why Miyazaki won’t say one way or the other.

In the Noh tradition, the main performer becomes the mask. When they wear it they can embody any age, gender, or social class. They can become anyone. They can become us. Perhaps that’s what No-Face is meant to be, a reflection of the most vulnerable parts of ourselves.

This is an updated version of an article first published June 5, 2020.

Related